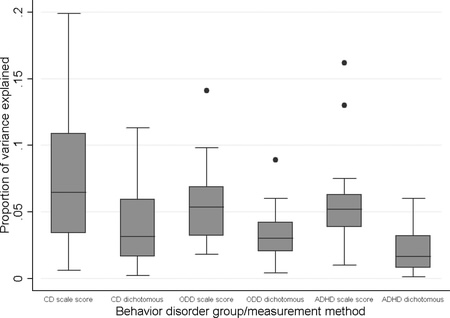

Figure 1 Distribution of proportion of variance explained estimates across all outcomes for different classifications of behavior disorder (continuous, dichotomous) and outcomes. The area within each box indicates interquartile range (IQR); the area within the whiskers indicates the lowest datum still within 1.5 IQR of the lower quartile and the highest datum still within 1.5 IQR of the upper quartile; closed dots indicate extreme outliers (>3 IQR). CD = conduct disorder; ODD = oppositional defiant disorder; ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. From Fergusson, J Abnormal Psychology, 2010 Nov;119(4):699-712.

This post started as a comment on Alte’s place. She describes herself as having attention deficit problems:

On the one hand, I have boundless physical and mental energy, bordering on hyperactivity. On the other hand, I’m constantly battling fatigue and struggle to concentrate on even the simplest of tasks. Especially on the simplest of tasks, in fact. I find mental challenges relaxing and energizing, and mental ease stifling and exhausting. I’m intelligent and bursting with creativity, but I’m a college dropout who still doesn’t know her phonics or math facts. Four times five is… is… do you have a calculator I could use? Let’s discuss Euclid instead, please, or allow me to read an economic journal to relax after the mental stress of multiplication tables.

I’m quite aware that there is pressure on many mental health workers to diagnose. Particularly if a child is having difficulties, the roving support teachers will have in their head a diagnosis before referring to a doctor. People arrive with a diagnosis.

And this is the difficulty. To the graph — this is data from the Christchurch Child development Survey. It is looking at conduct disorder, Attention Deficit and Oppositional Defiant Disorder. The first thing to note is the graph implies that NO one factor can explain more than 20% of the variance (in “all behaviours” — which was mainly adult criminal behaviour, unemployment and substance abuse). Secondly, there no one factor that is explanatory. Things over lap. If you use the DSM as a checklist, you don’t end up with one diagnosis — you end up with none or several.

In December 2009 there was an issue in Psychological Medicine that was completely devoted to a proposed structure of psychiatric classification. Given the issues that arise around symptoms reoccurring, it suggested that we look at clusters of conditions. Part of the data for this was a reanalysis of how many symptoms contribute to various syndromes. The externalising disorders therefore don’t fit neatly into the classification system:

From the perspective of the current DSM, our focus is primarily on substance dependence, antisocial personality disorder and conduct disorder because these disorders have received the most research attention in studies focused on evaluating aspects of an externalizing spectrum conceptualization. Specific features of other disorders may also be understood as elements within an externalizing spectrum; for example, hyperactive/impulsive aspects of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) may be more relevant than inattention; and the impulsivity aspects of borderline personality disorder (BPD) may be more relevant than instability in self-image

Krueger RF, South SC. Externalizing disorders: cluster 5 of the proposed meta-structure for DSM-V and ICD-11. Psychol Med. 2009 Dec;39(12):2061-70.

In children, all this is complicated by the reality of our education system. State education, despite efforts with the highly able and less able, is tuned for the majority of students — who by definition are of average ability. The highly bright often act differently, and this can be seen as abnormal.

The things that hunt with high intelligence (hyperfocusing and the associated inattention to cues, rapid processing, and rapid progress) lead to children being bored. And bored, intelligent children either tune out or do something. This can lead them being labelled wrongly.

Truly hyperactive children can appear to be oppositional. Oppositional children are often inattentive.

All of these groups may offend, distress, and disrupt the teaching space. Good teachers manage this. But, in this era of DSM, bad teachers reach for the diagnosis. And this leads to a need for as, Martyn Patfield has recently written undiagnosis.

A colleague commented recently that she spent a large proportion of her time ‘undiagnosing’ patients. I take her to mean that she challenges diagnoses which the patient has been given (and perhaps feels some attachment to) because the diagnosis is either clearly wrong or has little validity and also because the diagnosis is having a detrimental effect on the patient. Her use of the verb ‘to undiagnose’ has elements of humour and irony but it is interesting to think more about why it lingers as a useful word, even after the joke is over.Read More: http://informahealthcare.com/doi/full/10.3109/10398562.2010.539226